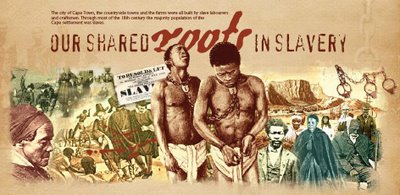

Commander Jan van Riebeeck first Dutch East india Company (DEIC) governor at the Cape of Good Hope started the practice of slavery at the Cape. His own household included slaves from Angola, Guinea, Abyssinia, Batavia, Madagascar and Bengal. The DEIC had a dedicated Slave Lodge for up to 1000 company slaves, alongside the main vegatable plantation (next to the modern day Parliament buildings).

A number of slaver ships operated out of Cape Town to bring in new slaves regularly. The names of these were the

Amersvoort, Leidsman, Voorhout, Eemlandt, Brak, Jambij and Meermin. In addition to these, slaver ships of many nationalities anchored in the Cape with 'cargoes' destined for Europe and the Americas. Some from amongst this 'cargo' were sold in the Cape. Those in the forefront of the slave trade included the Portuguese, Dutch, Danes, Swedes, French, Spanish, Arabs and coastal African collaborators. Until their about-turn the British were also in the forefront and they were joined by Americans, Russians and others. As time went on it became quite a free-for-all and included pirates too.

Many tragic sinkings of slaver ships occurred along our coast. In 1794 the slaver ship

San Jose was wrecked between Camps Bay and Oudekraal and 250 slaves were drowned. In a case similar to the famous Amistad mutiny by slaves, the

Meermin was wrecked on the South Coast near Arniston in 1766. I will leave this story for another posting in the future.